Tate Modern

To sell your television, your mismatched dishes and collections of clutter. To look upon your existence with the ruthlessness of a housefire: all broken chair limbs and charred remains littered with shampoo bottles. And with calm resolute to sift through these detritus comforts and tidily pile the shards is to understand the nature of transience.

I’ve lived in three large cities, four small cities, two big towns, several little towns, and one let’s-kick-up-some-dust-and-call-it-a-town kinda town. Walking down unfamiliar streets, I’ve felt the impossibility of familiarity. Studying the faces and bodies of strangers I’ve recognised the trace of lips and cheekbones so similarly etched in others.

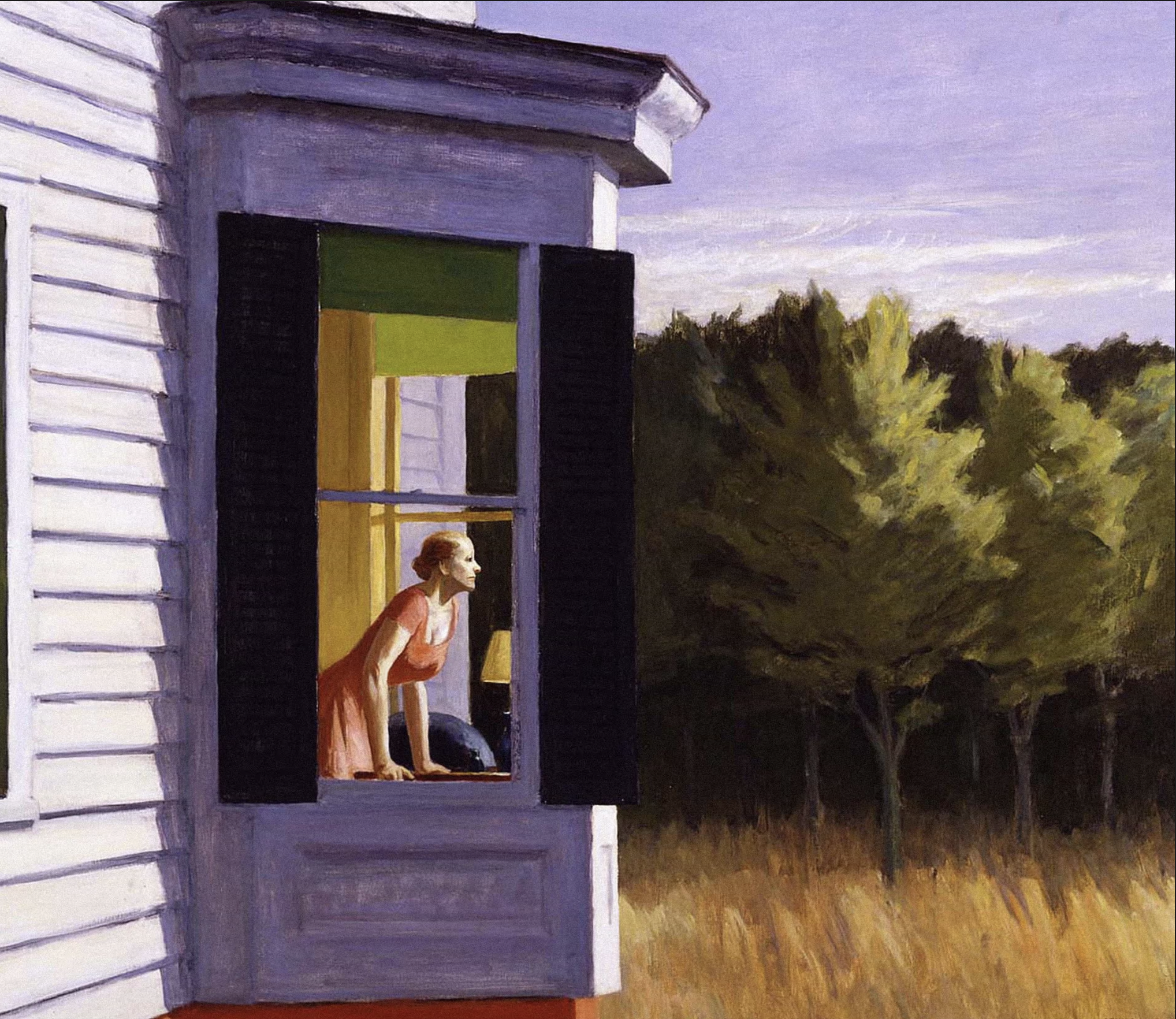

And when reading Jack Kerouac, listening to Joni Mitchell or viewing an Edward Hopper, I’m never really sure if it’s my lungs constricting with their residue of unity, my breath catching with a nodding understanding, or just somebody else’s who happens to look kind of like me.

In 1927, Edward Hopper painted Automat, depicting a lone woman dressed in coat, hat and gloves seated in a night café. There’s all the gritty goodness of an urban setting: the artificial glare of florescent lighting, both illuminating and reflecting the subjects’ solitude. She’s waiting, that tampering of minuscule time, with one glove off, one left on, while idly positioning and repositioning teacup into saucer.

With crossed legs and a downturned gaze, her expression is closed to the viewer. The voyeur, however, ascertains thoughtful mood and dramatic anticipation within the enmeshed void of transition.

Automat is one of Hoppers many iconic images bringing together “inside and outside… being there and not being there at the same time.” In other words, a fusing of aloneness, disconnect and abject separation into composite drama.

When I was twenty I broke up with a boyfriend in that hotly frenzied manner so near immaturity’s surface. I screamed, berated and fucked his countenance to the high heavens while he condescended, before shutting up, shutting out and taking off.

I took his leaving as opportunity to gather my meagre needs of clothing and assorted paintbrushes. Armed with potted plants, I left behind everything else including our cat Rita, the sleek white cat with one orange splotch on her belly, who always liked him best anyway.

In that moment of futile demise, of chucking my keys through the letterbox and absconding with the best bits of his CD collection, I became a case in point to “Hoppers brand of realism… so filtered and distilled that at times it can verge on abstraction.” That,“the real subject matter is the composition.”

In Summertime (1943), a young woman waits on stone steps in flimsy summery white dress. Nothing else is given, merely suggested: a breeze billowed curtain, a trace of anticipatory gaze. It’s the geometry of architecture, the angular stance and lemony-yellowflush of light that firmly situates the composition so trademark Hopper. The womans form, cool and singular against a colder still cement grey, experience and invite the viewer to experience the monumentality of isolation.

Hopper painted women alone in hotel rooms, houses alone in landscape and strange companions formally separated through device of elongated shadow, cutting light and exaggerated spatial dimensions. The effect is a possibility, gregarious in its ability to incite voyeuristic tendency.

Alone, the kind that leaves you gasping for breath, speech and sanity, that implores you to down a bottle of Valium and chase it with vodka is not present here. Here is noir desolation, bloated with moody anticipation. Hopper depicts that essential moment of separation and transition where dragging about a leach is no longer necessary.

Here is an aftertaste of that gluey desperation, mixed with dramatic composition. That, in leaving behind the linens in the cupboard and the orange juice in the fridge before chucking keys through the letterbox, you’ll find the familiarity of transience bathe you.